People often talk about “finding time” for creative work—as if somewhere between errands, messages, and endless scrolling, there’s a pocket of unused hours just waiting to be discovered. But that’s an illusion. Time isn’t something we stumble upon; it’s something we actively shape—and then we must show up inside it.

In Making Time, I argue that creativity isn’t an accident. It needs both mindset and structure. It means learning how to make time, not waiting to find it. That sounds simple, but it’s a radical reorientation of our relationship with our unstructured hours.

We shouldn’t structure every moment of our lives—but we should be mindful of how we use the time outside our obligations. Even when we think we're doing nothing, we're doing something. A walk. Meditation. Scrolling through social media. And sometimes, I’ll spend a day doing innocuous chores under the guise of "clearing my mind," only to realize I’m avoiding the actual work. It's not rest. It’s procrastination.

This tension—between setting conditions for insight and using them to delay action—is subtle and pervasive.

Jenny Odell, in How to Do Nothing, makes a compelling case for reclaiming our attention as an act of resistance. She argues that the platforms which dominate our lives are built to monetize distraction—to occupy the “in-between” moments of our days and flatten them into unconscious consumption. Odell’s version of doing nothing isn’t about laziness—it’s about cultivating deep noticing, relational attention, slowness. All of that resonates deeply with me. But I’ve also noticed how easily that form of “nourishing presence” can slide into something avoidant. I’m not always resting when I think I am. Sometimes I’m just not starting.

Oliver Burkeman, in Four Thousand Weeks, goes one step further: he frames our obsession with optimizing time as a form of denial—an attempt to outrun the discomfort of our limits. We tell ourselves we’ll start when we’ve cleared our inbox, when the weekend arrives, when the stars align. But real work starts not when conditions are ideal, but when we decide to begin—even with imperfect tools, even at the wrong time. This is basically what Making Time is about.

You’ve probably heard the infamous anecdote about how Sia wrote Rihanna’s “Diamonds” in about 15 minutes—while her cab waited outside. Or about how most Juice WRLD tracks were captured in a single improvised take, freestyled straight into the mic. There’s something remarkable about how creative clarity sometimes arrives all at once, within seemingly impossible parameters.

In this context I also think a lot about Imogen Heap’s Hide and Seek. During a late-night session, her computer crashed. All she had left was a four-voice DigiTech harmonizer. So she improvised. She sang the whole song in just a few takes, and built up the production in that one piece of hardware. And what came out was a totally singular piece of music—haunting, mournful, emotionally unguarded. A through-composed vocal, meandering like grief itself, layered and refracted through pitch shifting and vocoding. The whole song is just one voice, multiplied and altered to feel like a memory echoing back at itself.

It’s a form that’s since been imitated, sampled, interpolated—by pop stars, indie kids, TikTokers. This song is my favorite blueprint for how emotional clarity can arrive not through control, but through limitation. And it’s a valuable testament to something that’s easy to forget in a culture obsessed with optimization: you can’t control how long it takes to make your best work. Sometimes it takes a lifetime. Other times, it’s 15 minutes, or a single pass through the chorus.

The timeline isn’t yours to dictate. But the space you make for it—that is.

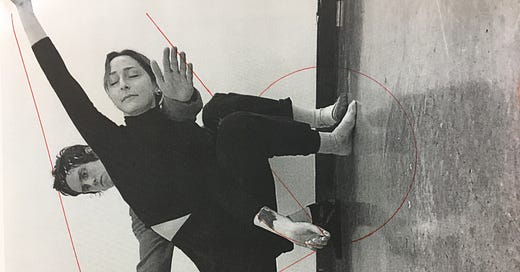

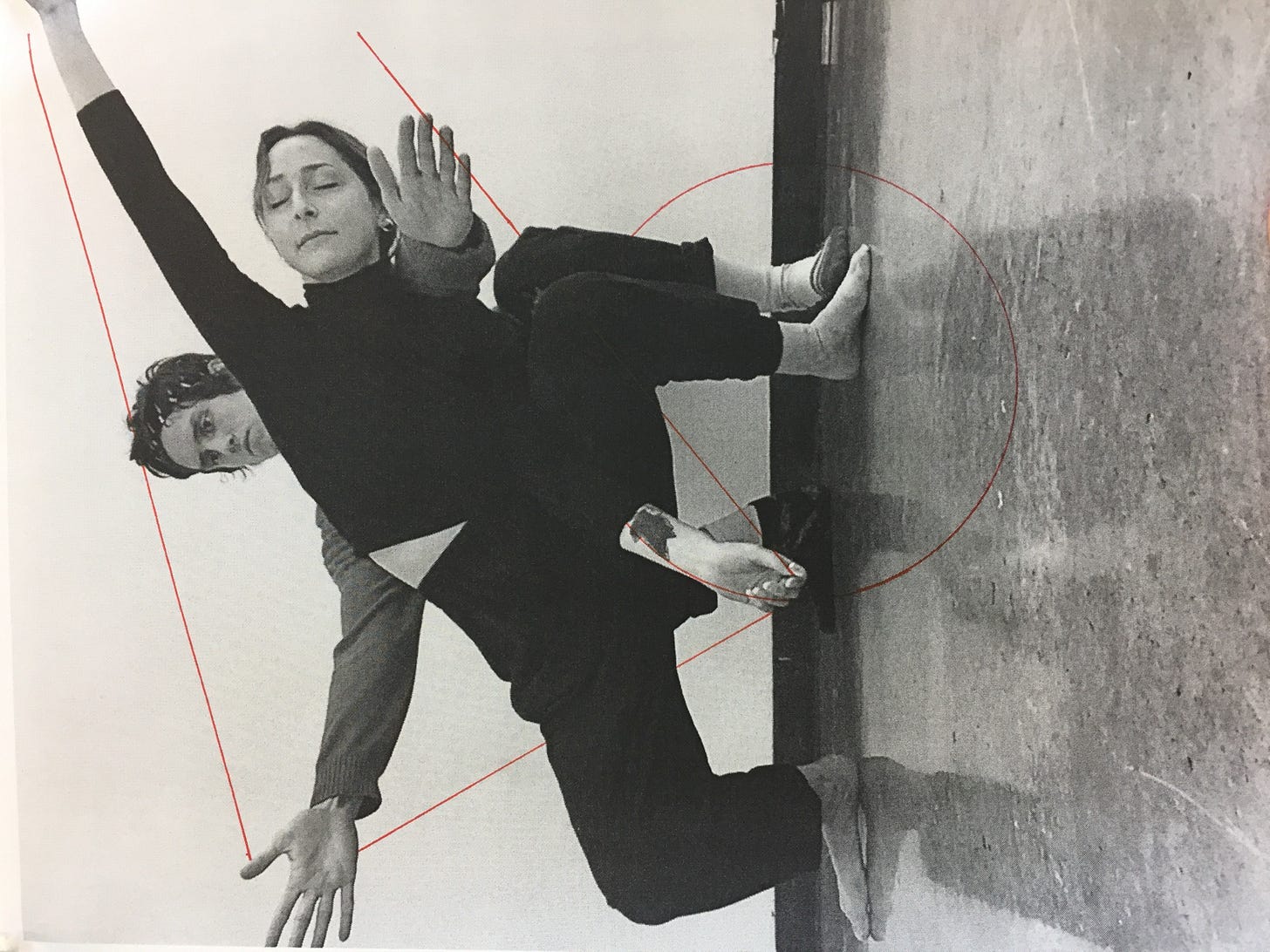

This is why ritual matters—not just in theory, but in practice. Twyla Tharp, in The Creative Habit, writes about “ritualizing the beginning.” She describes it as a reliable, repeatable gesture that initiates the creative act—laying out the tools, entering the room, putting on the same music. The content may change, but the signal remains: now we begin. You’re not waiting for inspiration—you’re building a system that invites it.

Sometimes, I give myself 30 minutes to make a full track. And somehow, the track happens. It’s never perfect, but it exists. The work always seems to meet me at the level of urgency I bring to it. Other times, I block out an entire day—and I spiral. Second-guessing, aimlessness, fear in the guise of “freedom.”

This isn’t a plea to rush your process. Some projects need slowness. But most of the work I actually finish—music, writing, even this book—comes from placing intentional limits around my time and trusting myself to act inside them.

That’s the real discipline: not just making time, but making good use of the time you’ve made. Ritual matters. Structure matters. But so does letting go. At some point, you have to move from preparing to participating.

This Friday, I’ll share the preface and introduction to Making Time, exploring how the book itself came to life—and why I wrote it the way I did. That post will be available to paid subscribers. If you want to read it early, you can upgrade your subscription.

No pressure—the Wednesday letters remain free. But if this resonates, I’d love for you to join in.

Until next time—trust the timeline. Not because it’s predictable. But because it’s yours. Thank you for reading.