the conditions of insight

on stillness, switching mediums, and why ideas don’t come when called

Last week, I wrote about the tension between giving advice and doing the work—the way knowledge, once embodied, becomes something else entirely. I want to stay with that idea, but shift the angle slightly. Not toward what we know or even what we do, but toward the conditions under which knowing becomes possible.

When I look back on the best ideas I’ve had—not just clever thoughts, but real shifts in understanding—I’m struck by how rarely they arrived on schedule. Insight, for me, doesn’t come from pushing harder. It comes from a subtle rearrangement of conditions. A change in light. A break in rhythm. A switch in materials. It’s almost never the result of direct effort, but of the environment around that effort softening just enough to allow something through.

This isn’t a new idea. Rick Rubin talks about it constantly: the importance of cultivating conditions for creative work, not forcing the work itself. Pauline Oliveros had her own term for it—deep listening—a way of attuning not just to sound, but to attention itself. Both insist that what we call creativity is not a resource to be mined, but a relationship to be tended.

For me, the most consistent conditions for insight are surprisingly mundane: morning dog walks, especially out in nature, driving and listening to music, things like that. There’s something about the motion, the looseness, the way my mind unspools when I’m moving without a goal. Ruminations that felt stuck begin to move. The inner monologue softens just enough for something quieter to speak. Ironically, this is also a space where capturing ideas becomes almost impossible. To stop, pull out my phone, and jot something down feels beside the point. It would puncture the mood. So I keep moving, knowing that not every good idea needs to be held onto right away. Some will return and some won’t. That, too, is part of the ecology of insight.

There are other places where insight hides for me: washing dishes, showering (obviously), biking cooking. What these moments have in common is a kind of soft focus—attention that’s present, but not narrowed. Not idle, but not aiming. A receptive state rather than a generative one.

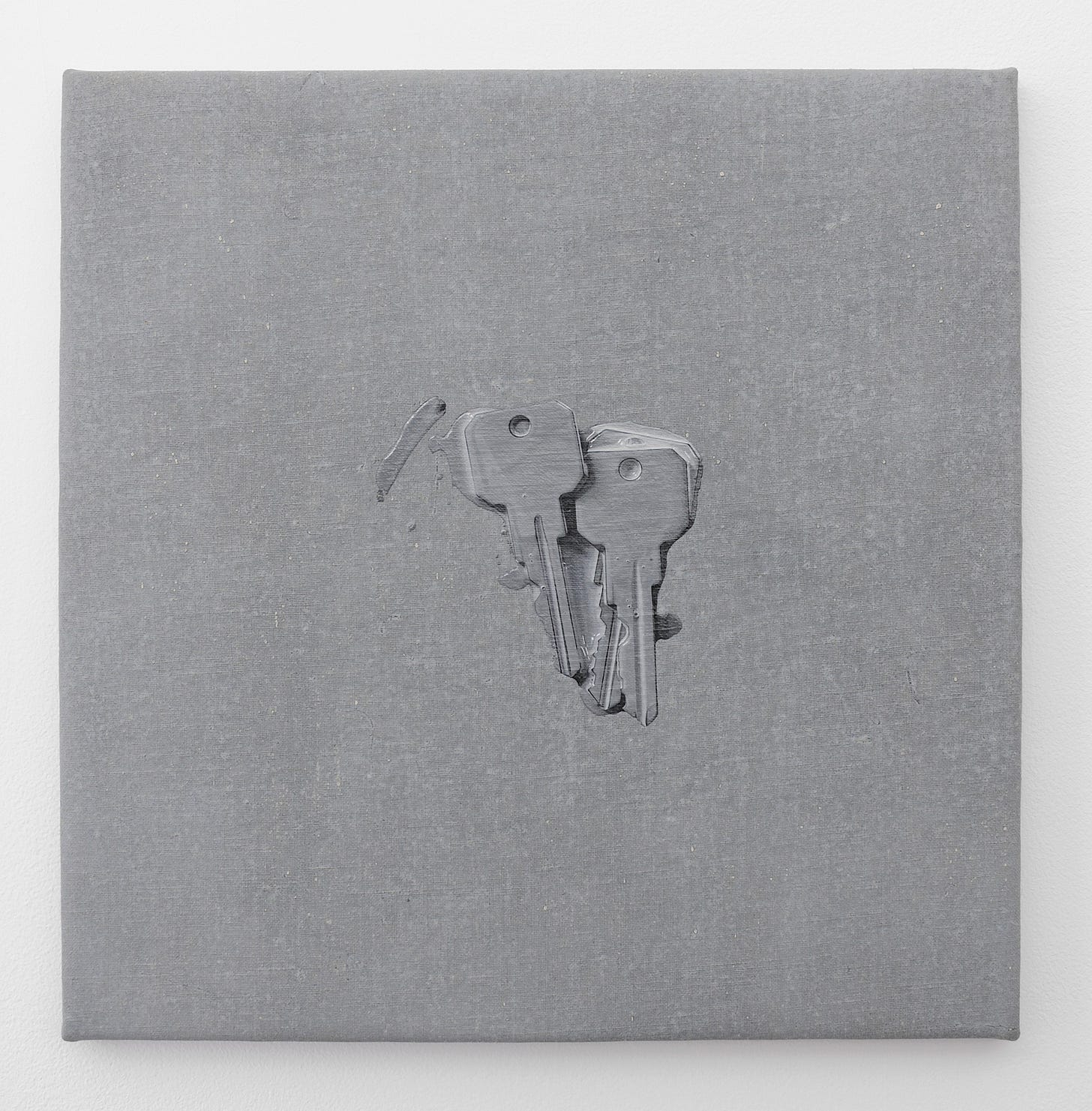

I also notice that switching mediums can often re-open insight. When a musical idea starts to feel too digital, I’ll step away from the DAW and sing the part I want to hear, or shift my attention momentarily to the organic sounds around me. Sometimes I write in order to figure out what I’m making. Sometimes I listen back to my own work from ages ago to try to ground myself in my own artistic context. Sometimes I DJ—reconnecting with sound through someone else’s curation. The shift in format dislodges whatever was stuck.

What all these things have in common is that they invite me back into the present—not to solve the problem, but to let it breathe.

There’s no perfect formula. That’s part of the point. What works for me might not work for you. The real practice is noticing what supports your perception. The environments. The cadences. The states of mind. Insight, after all, isn’t just an idea—it’s a shift in attention. A click of recognition. A quiet “oh” that arises not because you tried harder, but because you changed your stance.

So this week’s letter is a gentle nudge toward reflection: not just on what you’re working on, but how you’re positioning yourself in relation to your own insight.

A few prompts to explore:

When have you experienced a genuine breakthrough? What were the conditions—physical, emotional, temporal—that made it possible?

What elements of your current environment support your insight-making? Which ones might be crowding it out?

What happens when you change mediums? From digital to analog, from words to images, from composition to movement?

What kinds of conversation feed your creativity? What kinds drain it?

What is your version of deep listening?

Where do you go—not to “get ideas”—but to become someone who might receive them?

Insight is like sleep: you can’t make it happen, but you can make a bed for it to land in. Sometimes the most productive thing you can do is rearrange the room.