“You have the possibility with electronic music to generate any texture, in theory, and any sound. So why would any musician want to limit themselves? You want to work with the most powerful tools you can work with and, in the past, that may have been a piano or a guitar, but now, I think the power of software synthesizers is something all musicians would want to harness.” —SOPHIE

Making electronic music feels like total freedom. With the tools we have, we can transmute sound waves into emotion, sculpt with time, and craft immersive experiences out of thin air. We can represent sonic situations in nature with verbatim accuracy, and we can create otherworldly sounds, entirely unique our aesthetic priorities. I find this expanded universe of options, and the freedom it creates, to be exhilarating, sometimes to the point of overwhelm.

With infinite possibilities, why is staring at a blank session so daunting? Why does total creative freedom often result in so much unfinished work? For me, it’s a matter of structure.

Creative paralysis arrives when there are too many options and no system to anchor the process. In my practice, it's not freedom but constraints that unlock creativity. Structure focuses our attention, reduces overwhelm, and forces us to solve problems in ways that total freedom cannot. Across mediums, artists thrive under creative limitations: Dr. Seuss’s Green Eggs and Ham was written using just 50 words. Ernest Vincent Wright’s novel Gadsby famously excludes the letter “E.” Yves Klein created a series of works using only a single shade of blue. These constraints didn’t hinder creativity—they enhanced it.

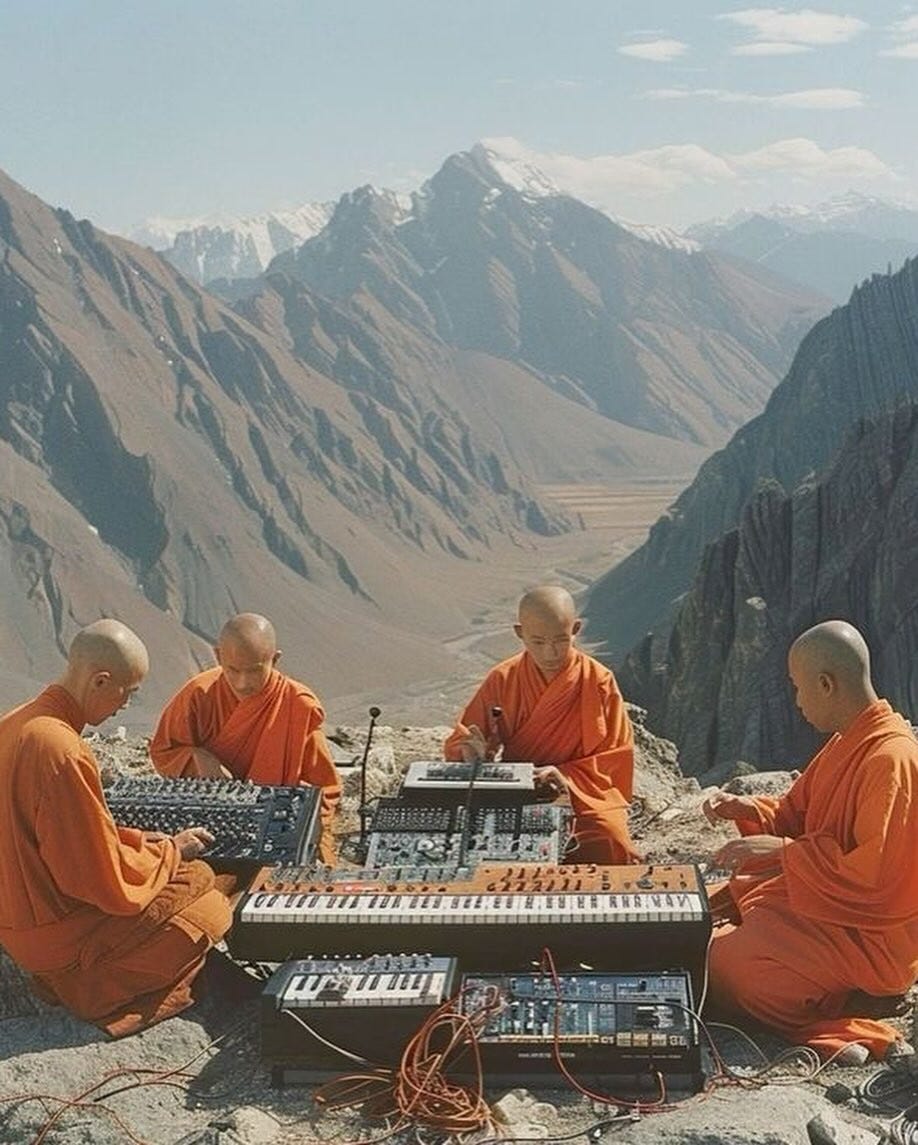

The Modular Rig

In 2021, James Blake released Friends that Break Your Heart, his most polished album to date. The songs were meticulously written and delivered with ultimate vocal clarity. He worked with a topline vocal melody writer, collaborated with the likes of Metro Boomin and SZA, and the music video for it’s lead single, “Say What You Will,” featured a number of intentional comparisons to FINNEAS (the brother and producer of Billie Eilish). This, to me, felt like the peak expression of Blake’s deep and expensive industry connections, his audition for mainstream popstar status. I didn’t totally dislike the album, but it didn’t connect with me as much as what he did next.

The next album he released, Playing Robots into Heaven announced itself with a single that didn’t feature his voice at all. “Big Hammer” is a gnarly, buzzy club track that unfolds in an extended modular synth jam moving around a looping vocal sample of the Ragga Twins. The album that followed this release was composed entirely on a custom modular rig that Blake had cobbled together over the last few years.

For those not familiar with modular synthesis, it’s a system of electronic hardware units (drum machines, synths, samples, effects etc.) that can be connected to one another in various configurations using patch cables. A modular rig looks more like an electrical motherboard than a musical instrument, and its a famously difficult protocol for producing the kind of music most people enjoy. Think: abstract, ambient ‘bleep bloop’ type beats.

The album is beautiful. It is so much more sonically focused, and narratively adventurous than its predecessor. It is the result of deliberately imposed creative constraints—a sharp contrast to the world of infinite resources he’d drawn on in its predecessor.

Flow

When every possibility is open, we’re faced with the overwhelming task of deciding where to begin. This is what the (awesomely named) psychologist, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi describes in his book Flow: the Psychology of Optimal Experience. Csikszentmihalyi developed the idea of ‘flow state’ within the framework of Positive Psychology, an ongoing study into human happiness. Having experienced the traumas of war in his youth, he was convinced that happiness was an internal state that could be created with practical psychology.

One of the keys to happiness and therefore longevity, was spending time in a state of optimal experience. This is known as Flow. One crucial aspect of Csikszentmihalyi’s theory of flow is that, without a clear structure to channel our attention, it’s nearly impossible to reach the immersive state of focus where our best work happens. Csikszentmihalyi emphasizes the importance of maintaining a balance between boredom and overwhelm. When a task is too simple, we become disengaged; when it's too complex, we feel anxious. The optimal experience occurs when challenges are well-matched to our skill level, keeping us fully engaged and motivated.

Creative Containers

Constraints help us enter the state of flow by reducing distractions and unnecessary decisions. In Flow, Csikszentmihalyi notes that focus thrives when clear goals and structured challenges align with our skills. A creative system—a repeatable framework, an interconnected web of limitations and prompts—removes unnecessary decision-making, allowing us to concentrate fully on the work itself. In other words, systems combat decision fatigue.

Research in practical psychology indicates that the quality of our decisions deteriorates after making numerous choices, leading to impulsive or avoidant behaviors.

In my own work, I find a lot of ideas through play and improvisation. When I sit down to make music, I do not want to spend time browsing for samples, auditioning instruments, designing sounds or configuring effects chains. All of these elements are necessary, of course, but I would prefer to get started on the actual music making before doing any of this. The quality of my creative decisions will be reduced if I’ve already exhausted my mental resources searching for the “perfect” kick drum sample for a song that doesn’t even exist yet!

Creative blocks arrive when we get bored, overwhelmed or distracted. My solution to this was to create a system where making music is just easy enough and just hard enough to keep me engaged throughout the process, from sound selection, to composition, to arrangement, to mixing. This system, which I’ve made into a template in Ableton, is wide open enough to encourage free play and active experimentation, but limited enough to keep me focused, engaged and excited to problem-solve.

Speed and Perspective

Using a creative system that is aligned with an overarching goal is a great way to consistently finish music. In my case, my goal is to make music that is qualitatively comparable to the music that I love. I’m reaching at a feeling or emotion that I’ve heard in some other music. I want my skills to catch up to my taste. I’m pursuing ultimate fluency in my own musical language.

Working quickly is a crucial factor here. In Processing Creativity, Jesse Cannon emphasizes the importance of maintaining momentum to preserve the initial excitement of a project. He suggests setting deadlines and limiting the number of revisions to keep the creative process moving forward.

When start a new project, my immediate goal is to make a piece of music that I can evaluate on its artistic merits, and further refine from there. It’s important that I get there quickly in order to maintain perspective. The longer we linger on a piece, the harder it becomes to understand it from the perspective of the listener.

Many have called this “demo-itis.” Artists will become emotionally attached to a work in progress because they’ve spent more time listening to it than they have working on it. Listening to an unfinished piece over an over again can distort your opinion of the work: your ears can become accustomed to something you’d otherwise want to change. You can get too attached some ideas and pass over others that might be worth bringing forward.

This is why it is important to cultivate your listening skills in alongside your production skills. The more perspective(s) you’re able to have on your own work, the better creative choices you’ll be able to make.

Adaptive Systems and Chaos

A system is not a formula and it doesn’t have to be rigid—it just needs interconnected steps that guide a certain process. Like in James Blake’s modular rig, an idea or signal can go in many different directions, as long as there’s a pathway. Creating such pathways for ideas to move around and take form is the creative process.

My all-purpose Ableton template is entirely organic to my way of working. It gets continually refined as my creative process expands to incorporate what I learn.

I developed it by pulling together techniques I use most. The objective of using a template is to put me in a mental environment where I make my best work. The tools I like to use are ready at hand: instruments are loaded, tracks are labelled, effects chains are already set up (but de-activated). There’s a space for sonic reference material, an auxiliary sidechain channel and an arrangement lane that helps keep me conscious of repetition and variation, of tension and release.

I encourage you to develop a repeatable system, not to narrow, but to expand your creative practice. If it becomes too limiting—if it’s producing work that all sounds the same—you can always incorporate an element of chaos. Many producers use creative resampling to gain new perspectives and move their work forward. You might try exporting a track, chopping it up and using it as the samples for an entirely new piece of music. If melodies are too repetitive—or you simply don’t find them interesting—you might experiment with a MIDI effect that randomizes the certain notes. This chaos phase within an existing system can disrupt predictability while keeping the benefits of a structured workflow.

Use Mine // Make it Yours

In my own music practice, I’ve found this balance invaluable. What I want to do is make music right at the edge of my own competency. I know what to do next, but I don’t know exactly what will happen. This might also be thought of as exploring. If you make music, take my template, and turn it into whatever best suits your way of working. Work with it, and refine it so that it works better. I can say with certainty that having a systematized approach to your work will lead to more, and better, music. As for how that system comes into being and what you use it to make: the possibilities are still endless.

What I’m listening to

10 new songs, updated weekly

Items of Interest

James Blake talks about the making modular music and all kind of other stuff on tape notes

Last week, I wrote about resisting professionalism, and staying amateur.

Next week I’m going to Scotland. Send me recommendations for Glasgow and Edinburgh